“Poetry and Beyond”

Yingdi Sun Piano Recital

National Centre for the Performing Arts (NCPA), Beijing · August 10, 2019

Overview

Returning once again to the National Centre for the Performing Arts, pianist Yingdi Sun presented an evocative solo recital titled “Poetry and Beyond.” The program journeyed through Brahms’s introspective late works, Ravel’s visionary Gaspard de la Nuit, and Liszt’s lyrical and virtuosic masterpieces — a traversal of Romantic intimacy and transcendence.

The concert reflected Sun’s mature artistry: profound in emotion, yet lucid in structure. His performance illuminated the poetic threads that connect composers across eras — the quiet tenderness of Brahms, the dreamlike sensuality of Ravel, and the spiritual passion of Liszt.

Program

Johannes Brahms (1833–1897)

Six Piano Pieces, Op.118

I Intermezzo in A minor — Allegro non assai, ma molto appassionato

II Intermezzo in A major — Andante teneramente

III Ballade in G minor — Allegro energico

IV Intermezzo in F minor — Allegretto un poco agitato

V Romance in F major — Andante—Allegretto grazioso

VI Intermezzo in E-flat minor — Andante, largo e mesto

Three Intermezzos, Op.117

I Andante moderato (E-flat major)

II Andante non troppo e con molto espressione (B-flat minor)

III Andante con moto (C-sharp minor)

Maurice Ravel (1875–1937)

Gaspard de la Nuit, M.55

I Ondine

II Le Gibet

III Scarbo

Robert Schumann (1810–1856) / Franz Liszt (1811–1886)

Widmung (Dedication)

Franz Liszt (1811–1886)

Sonetto 104 del Petrarca, S.161 No.5

Liebestraum No.3 in A-flat Major, S.541

Mephisto Waltz No.1, S.514

Program Notes Highlights

The recital booklet featured Sun’s own reflections on each work:

Brahms: Three Intermezzi, Op.117 — described by the composer as “lullabies to my sorrows,” these pieces embody an autumnal tenderness and deep humanity.

Ravel: Gaspard de la Nuit — based on Aloysius Bertrand’s surreal poetry, the set portrays the seductive water nymph Ondine, the haunting stillness of Le Gibet, and the grotesque, flickering specter Scarbo.

Schumann–Liszt: Widmung — a love song transformed by Liszt into a hymn of exultation and devotion.

Liszt: Petrarch Sonnets & Liebestraum — music of idealized love and spiritual yearning.

Artist

Yingdi Sun — Piano

Gold Medalist of the 7th International Franz Liszt Piano Competition (Utrecht, 2005), Yingdi Sun is renowned for his interpretative depth and luminous tone. A frequent guest artist at the NCPA, his performances have been praised for combining structural clarity with expressive warmth — embodying both intellectual precision and poetic sensitivity.

Venue

National Centre for the Performing Arts, Beijing · Theatre Hall (Small Theatre)

Reflections by Yingdi Sun

“Who recalls the west wind’s lonely chill?

Falling yellow leaves close the sparse window;

I stand at sunset, lost in thought of what has passed.

Do not wake me from drunken slumber —

Let the fragrance of tea and books linger,

For only later did I know those moments were rare.”

— from Nalan Xingde’s “To the Tune of Stream-Washed Sand”

Memory, when touched by words, stirs the soul.

Just as the poet Li Shangyin wrote, “This feeling can only be recalled, not relived,”

Nalan’s verse “Only later did I know those moments were rare” speaks even deeper.

The first stanza flows with tenderness — a solitary figure standing under the setting sun,

while the second turns inward, sketching warmth and quiet reflection.

Those fragments of life dissolve like smoke;

only in hindsight do we recognize that time’s fading traces are what give it weight.

If tonight the wind stirs again, perhaps the bridge of magpies will not be built after all.

And yet, if every encounter in life is a reunion after long separation,

then is not every reunion, too, a farewell in disguise?

Like Nalan Xingde, Brahms was a poet of “things gone by.”

This intermezzo, serene yet inwardly unfolding, is a song of his own life —

a meditation on the tenderness of parting,

echoing the realm of Nalan’s verse:

“Falling yellow leaves close the sparse window;

I stand at sunset, lost in thought of what has passed.”

— Yingdi Sun, July 2018, Shanghai

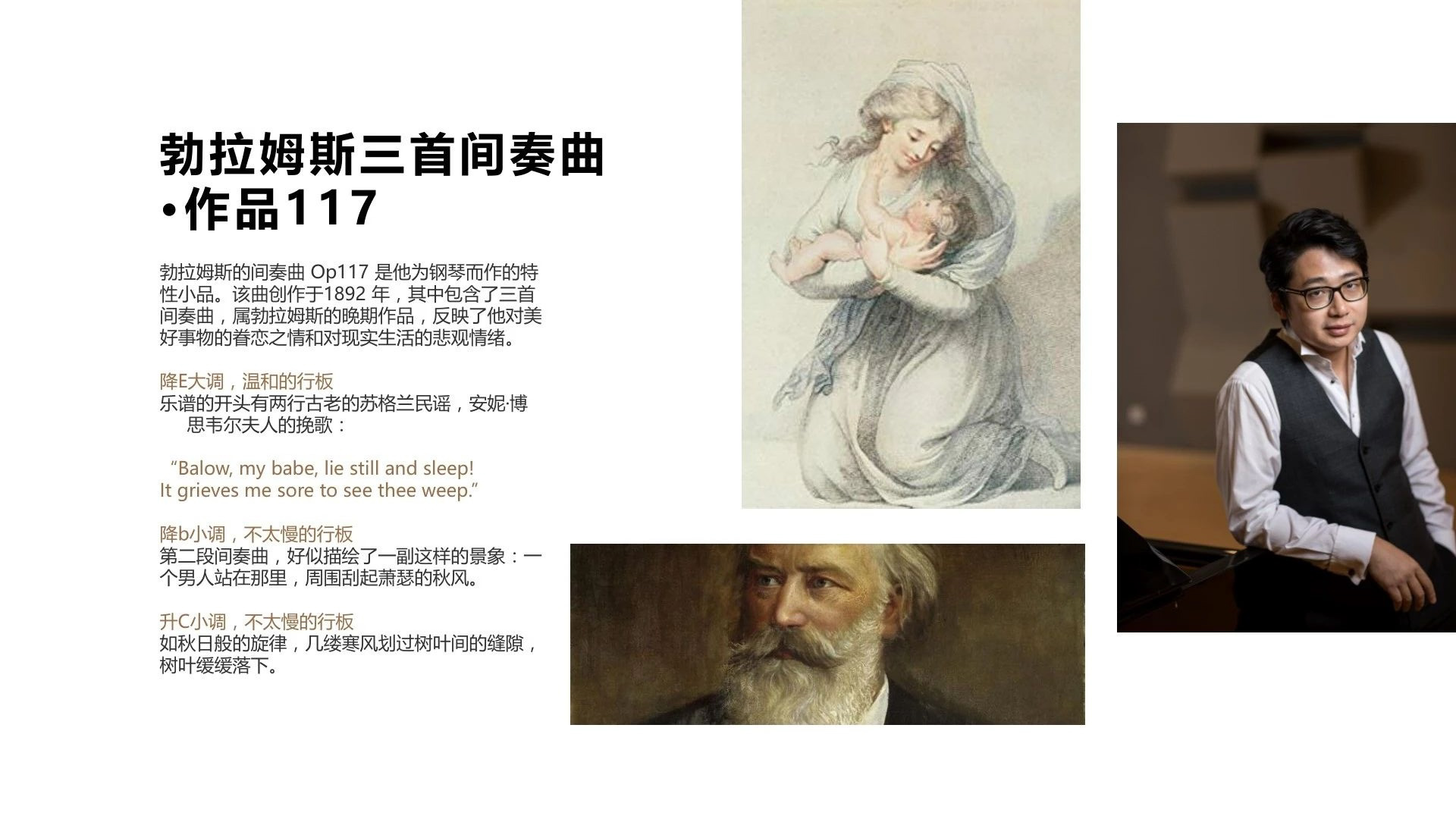

Brahms’s Intermezzi, Op.117, are character pieces written for piano in 1892. Comprising three intermezzos, these late works of Brahms reveal both his deep tenderness toward beauty and his quiet melancholy toward the realities of life.

No.1 in E-flat major – Andante moderato

The score opens with two lines from an old Scottish lullaby, Lady Anne Bothwell’s Lament:

“Balow, my babe, lie still and sleep!

It grieves me sore to see thee weep.”

No.2 in B-flat minor – Andante non troppo e con molto espressione

The second intermezzo seems to depict such an image:

a solitary man standing by the window, as the bleak autumn wind stirs outside.

No.3 in C-sharp minor – Andante con moto

Like a melody of autumn, a few cool gusts brush through the seams of the leaves,

and the falling leaves descend softly, like a sigh fading into silence.

“Gaspard de la Nuit is the pseudonym of the Devil himself —

it was he who gave me those poems of infernal craftsmanship.”

Aloysius Bertrand

Gaspard de la Nuit is Ravel’s set of three piano poems, composed in 1908 and inspired by the writings of Aloysius Bertrand.

This masterpiece is celebrated for its poetic imagination and its staggering pianistic difficulty —

a “realistic dream,” a world of darkness and terror revealed through refinement and precision.

Ravel brought Bertrand’s poetry to life, employing a visionary and painterly approach to sound —

a fusion of surreal imagery and vivid atmosphere.

Monsters and witchcraft, shadows and water nymphs, gallows and moonlight —

though its technical demands are extraordinary,

the work remains an unparalleled artistic achievement.

By expanding the expressive reach of the pianist’s two hands,

Ravel transformed the piano into a medium of visual illusion and emotional tension.

A master of sonic architecture, he combined the precision of craftsmanship with a painter’s imagination,

creating auditory visions of tangible reality.

Nearly all pianists regard Gaspard de la Nuit as both terrifying and mesmerizing —

a study in transcendent technique,

and a musical reimagining of Bertrand’s haunting poetry.

Each movement bears its own distinct color:

Ondine for its lyrical shimmer,

Le Gibet for its chilling stillness,

and Scarbo for its dizzying virtuosity.

Patrick, the tall and thin porter, led me into the descending corridor beneath the hotel.

The last trace of sunlight broke as the heavy door closed behind us.

Down the steps stretched a long passage; on one side, an iron gate.

In the dim light it was hard to tell whether the space beyond was a wine cellar or a crypt.

It was a rainy winter day.

When my fingers brushed against the rusted iron door, Patrick lit a candle beside him and pointed to a mural on the wall—

a portrait of Ravel.

I still remember how goosebumps rose all over my body.

This was not the kind of sensation that words like “romantic” or “sublime” could describe.

It was something unspeakable — an astonishment wrapped in darkness and the unknown.

Perhaps in that moment, I finally understood:

the ghosts in Ravel’s music are not inventions,

but awakenings of the most delicate perceptions of the human soul.

If Bertrand’s Gaspard de la Nuit was a dream of literature,

then Ravel’s Gaspard is its nightmare made real.

He does not explain fear — he breathes it.

He lets those spirits and visions take form again between the notes.

The music pulses like a faint light beating within a desolate heart: deep, cold, and irresistibly alluring.

For me, this piece is not merely the ultimate test of pianistic technique;

it is a confrontation with the self —

lonely, obsessive, and transparent,

like a mirror reflecting one’s own soul.

The closer you approach it,

the more you are forced into an almost unbearable honesty.

— Yingdi Sun, Winter 2018, Shanghai

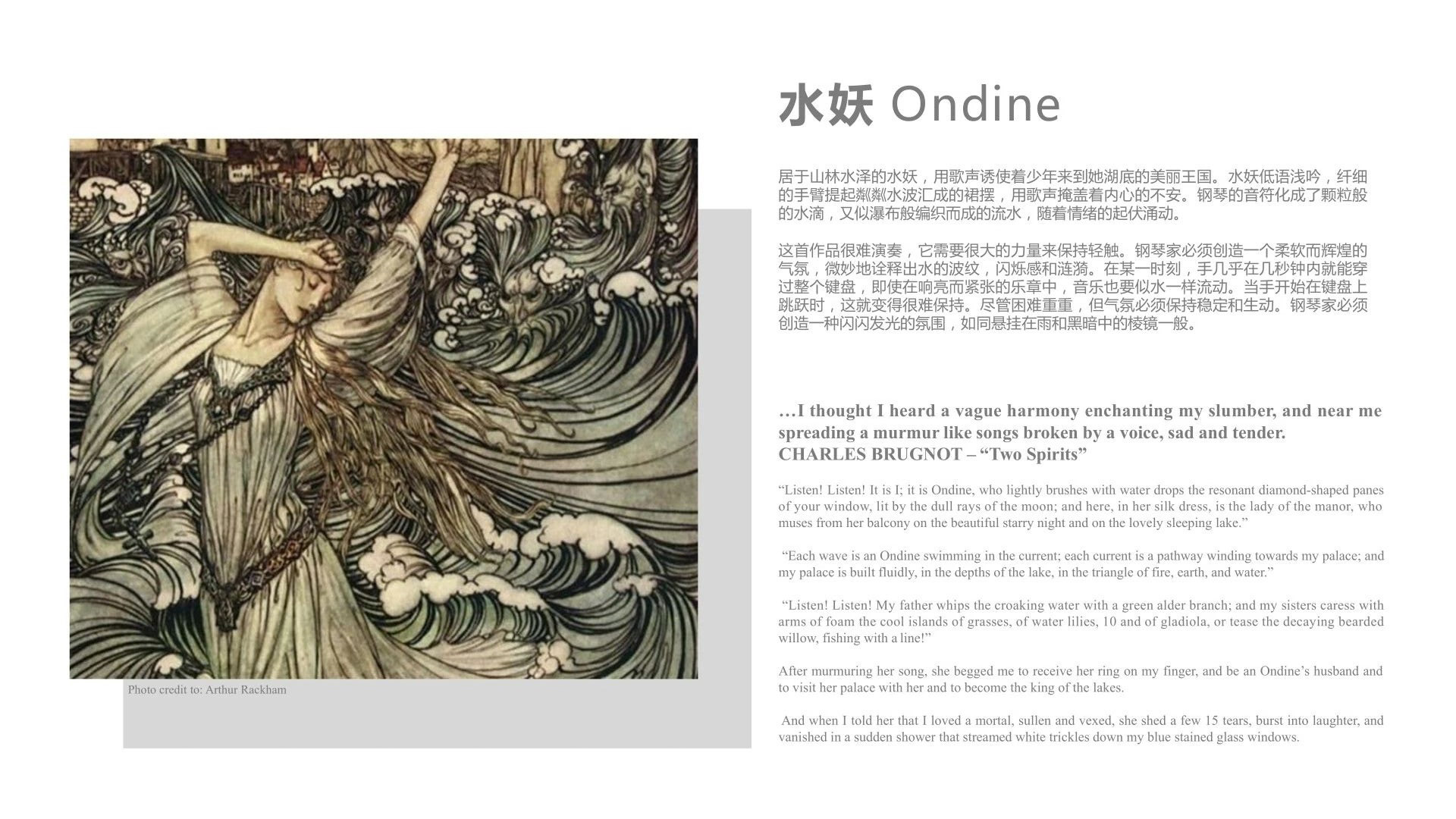

The water nymph who dwells in forest streams and mountain lakes

sings to lure the young man into her crystal kingdom beneath the waters.

Her voice is soft and enticing; her slender arms brush the rippling waves,

while her song glimmers like drops of liquid light,

flowing and shimmering with the movement of sound.

This piece is among the most difficult to perform —

it demands immense control to preserve a sense of lightness.

The pianist must create a supple, undulating current of air,

capturing the shimmer and translucence of the nymph’s voice.

At certain moments, the hands must merge into a single breathing motion;

even in the highest, most radiant registers,

the sound must flow like water.

When the hands leap across the keyboard, the motion must feel organic —

not an act of virtuosity, but an extension of breath.

The music must be alive.

The pianist’s task is to conjure a glimmering atmosphere,

like moonlight rippling across the dark surface of a lake.

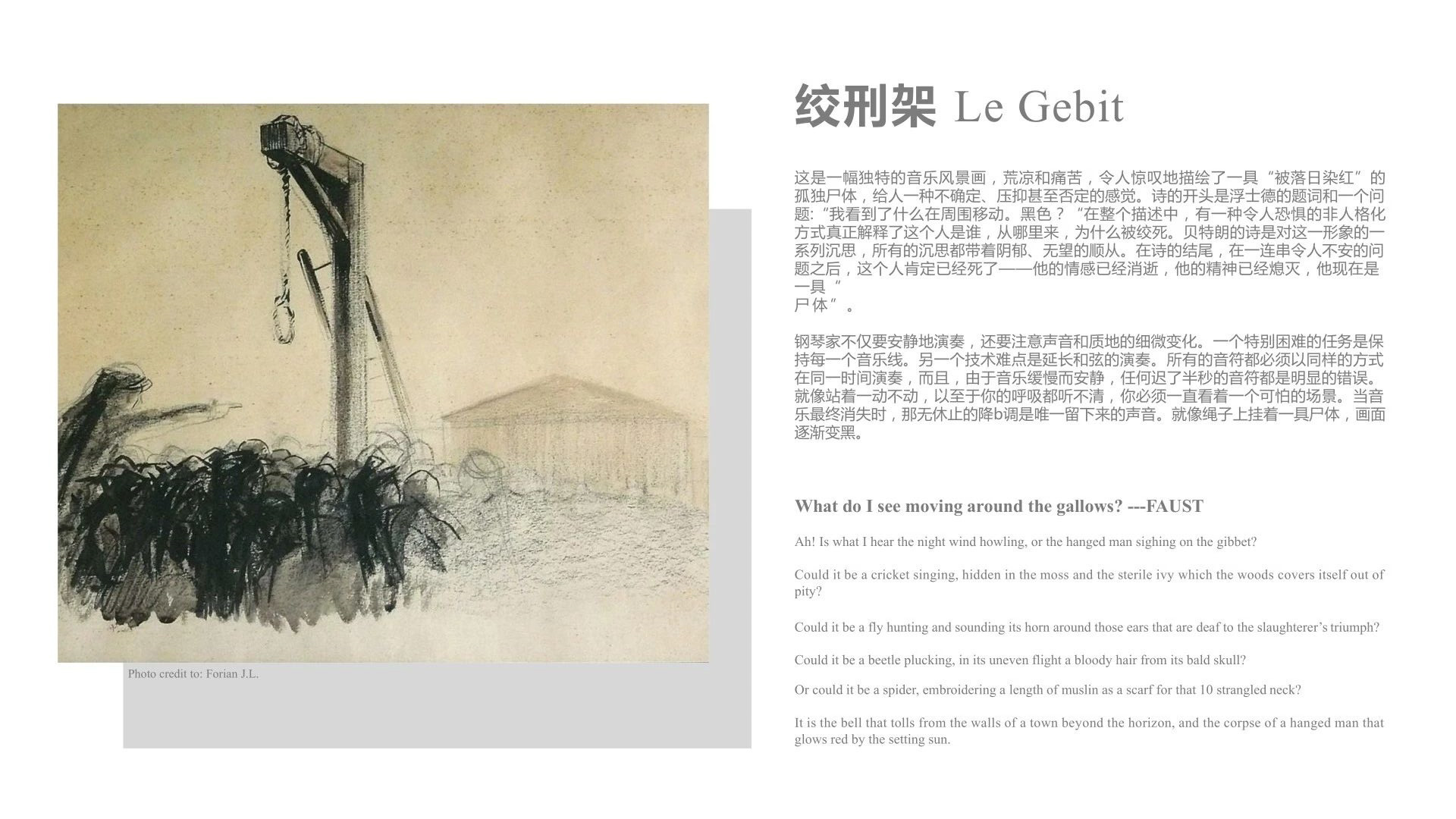

This is a unique musical landscape — bleak and resonant,

an astonishing depiction of a “murdered suicide,”

a solitary corpse suspended between sound and silence.

It gives a sense of uncertainty, oppression, and negation.

The poem opens with Faust’s question:

“What do I see moving around the gallows? Black? Rust? Trembling?”

There is a haunting personification at work here —

a meditation on who this man was,

what filled his heart,

and why he was condemned to hang.

Bertrand’s poetic tone recurs throughout the Gaspard cycle:

each contemplation shrouded in melancholy, despair, and fatal stillness.

By the poem’s end — after a sequence of disturbing reflections —

the man is surely dead.

His emotions are gone, his spirit extinguished.

He is now nothing but

a corpse.

The pianist must not only play quietly,

but attend to the most delicate changes of tone and texture.

One of the greatest challenges lies in sustaining every line of sound —

and in maintaining the resonance of every chord.

Each note must be played as part of a single, breathing whole.

Because the tempo is so slow and subdued,

clarity and continuity become the true test of endurance.

It is as if you are standing motionless,

watching time itself unfold in front of you.

When the music finally fades,

the endless resonance is the only sound that remains —

like the echo of a corpse swaying from the gallows,

as the image dissolves into darkness.

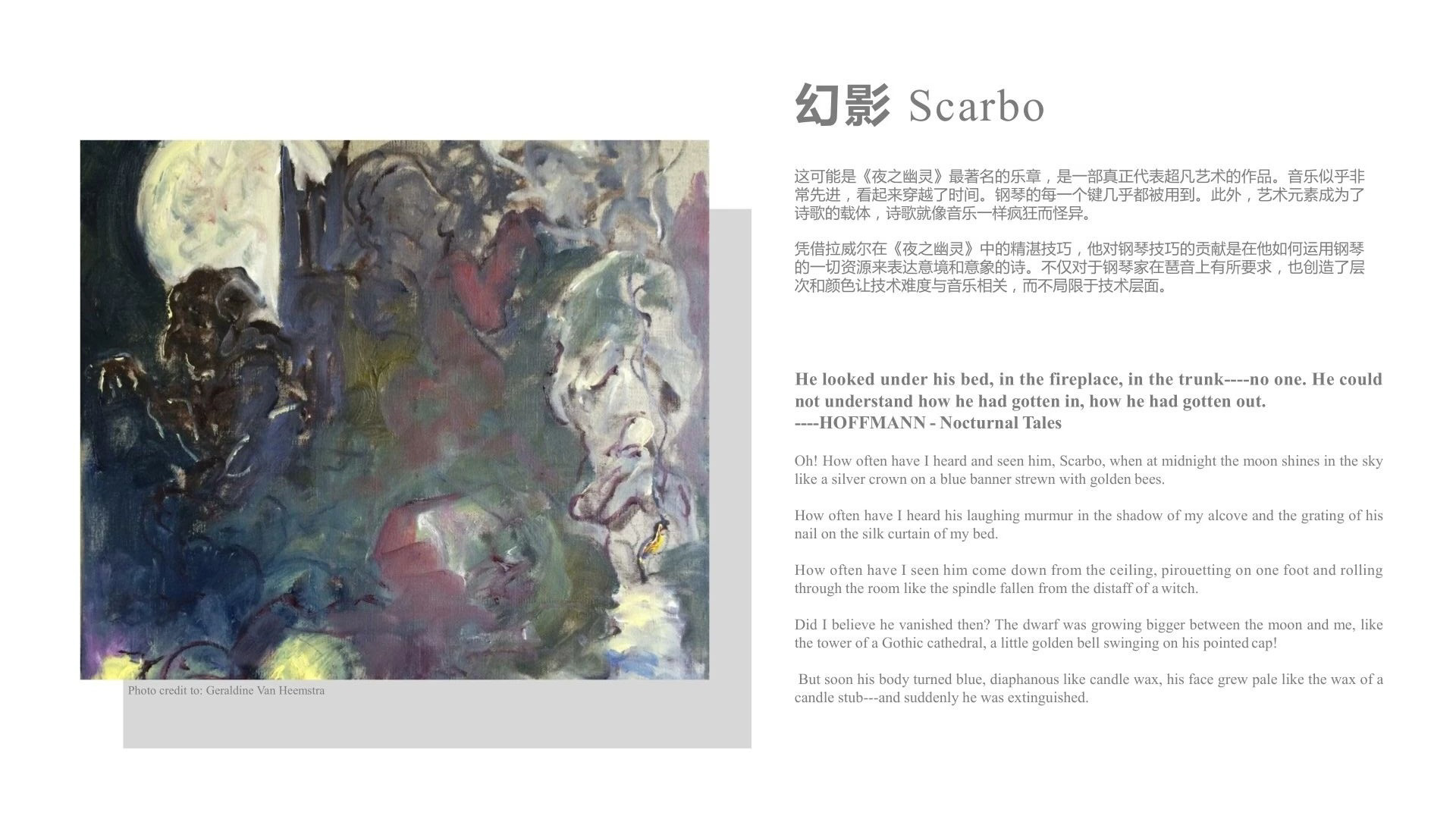

This is perhaps the most famous movement of Gaspard de la Nuit —

a work that truly transcends virtuosity and enters the realm of art.

The music seems to move irrationally through time;

nearly every key of the piano is employed.

Here, artistic imagination itself becomes the vessel of poetry —

its spirit flows through the music as seamlessly as sound and silence.

Through Ravel’s unparalleled technical mastery,

Scarbo reveals his most visionary achievement:

not in the brilliance of sheer difficulty,

but in his poetic use of every pianistic resource to evoke imagery and atmosphere.

Each gesture, each sound color, each layer of resonance

serves to fuse technique with expression —

transforming virtuosity into vision.

On September 12, 1840, Robert Schumann and Clara finally married in a village church near Leipzig.

Their union, long opposed by Clara’s father and Schumann’s former teacher Friedrich Wieck,

had been delayed for four years and even brought to court.

On their wedding day, Clara wore a wreath of myrtle — the traditional symbol of love —

and Schumann presented her with his Myrthen, Op.25, a cycle of 26 songs.

The very first of these, Widmung (“Dedication”), was his musical offering to her.

Set to a poem by Friedrich Rückert, Widmung expresses Schumann’s passionate love for Clara.

The melody is both tender and ardent, radiating warmth and sincerity.

Its outer sections in A major convey joy and vitality,

while the central E major section turns inward — serene, lyrical, and deeply heartfelt.

The text declares: “You are my peace, you are my heart.”

Indeed, it is the truest form of dedication.

Franz Liszt’s transcription for solo piano is one of the most celebrated Romantic paraphrases ever written.

Expanding Schumann’s original, Liszt enriches the texture with sweeping arpeggios and brilliant sonorities,

while maintaining the song’s emotional intimacy and clarity.

To perform it well requires not only technical mastery —

balancing layered voicing and seamless phrasing —

but also profound emotional sensitivity,

where every note breathes devotion.

You are my soul, you are my heart,

You are my bliss, O you, my pain;

You are my world in which I live,

My heaven you are, in which I float.

You are what raises me sublimely,

My good spirit, my better self!

O you, my grave, into which

I have laid my sorrow forever.

You are repose, you are peace,

You are bestowed upon me from Heaven.

That you love me makes me worthy,

Your gaze transfigures me before myself,

Lifting me higher through your love—

My good spirit, my better self!

Francesco Petrarch, the great Italian poet and scholar of the Renaissance, is revered as the “Father of Humanism.”

He brought the sonnet to artistic perfection, giving rise to a new poetic form now known as the Petrarchan Sonnet.

Petrarch’s love for Laura was purely Platonic — an idealized, spiritual affection, never acted upon.

After meeting her once at the age of 23, he continued to write about her for over twenty years, until he was 47.

These poems were later compiled into two parts: In vita di Laura (“While Laura lived”) and In morte di Laura (“After Laura’s death”).

In these sonnets, Petrarch elevates love to the divine: his passion is at once sacred and human,

filled with both adoration and anguish, longing and serenity.

His language, noble and luminous, reflects the Renaissance spirit of emotional introspection and expressive beauty.

The Petrarchan sonnet thus stands as one of the highest achievements of European lyric poetry —

a bridge between spiritual devotion and human emotion.

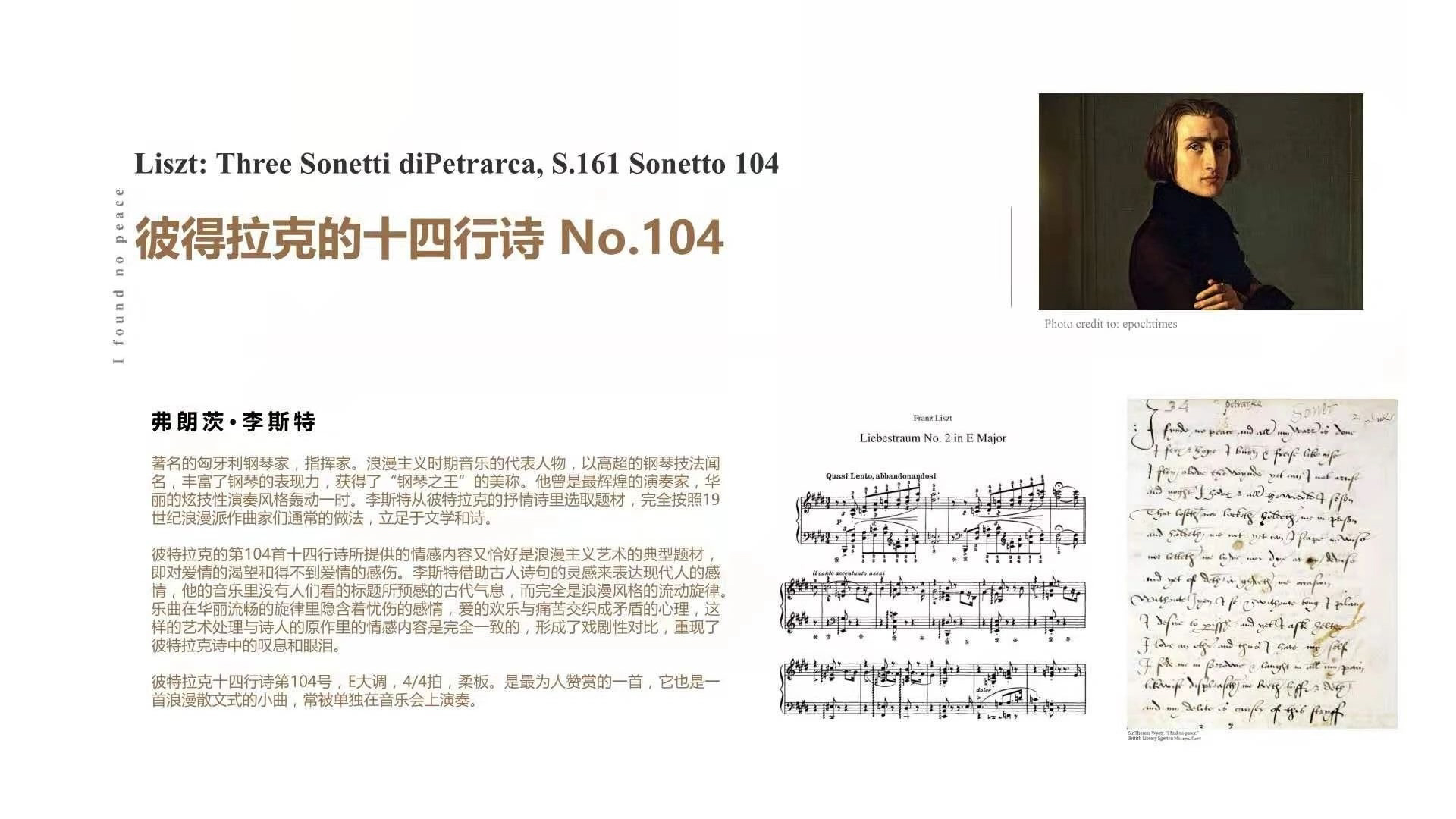

The renowned Hungarian pianist, conductor, and composer Franz Liszt was a towering figure of the Romantic era,

celebrated for his transcendental piano technique and unmatched expressive range — earning him the title “King of the Piano.”

A performer of dazzling brilliance and emotional depth, Liszt often drew inspiration from poetry and literature,

transforming written verse into vivid soundscapes that embody the Romantic ideal of fusing art forms.

The emotional theme of Petrarch’s Sonnet No.104 — the pain of unrequited love — perfectly mirrors the essence of Romanticism.

Through the lens of Petrarch’s verse, Liszt reimagines this longing in a deeply personal and spiritual way,

his music breathing with the same passion and turbulence found in the poet’s words.

It unfolds through striking contrasts of tenderness and tension,

embodying the inner conflict between love and despair.

This dramatic interplay of emotion gives the piece its structural and expressive intensity,

transforming the poetic lament into a musical confession.

Composed in E major, marked Andante (4/4 time),

Sonnet No.104 is widely admired for its lyrical beauty and emotional depth.

Among the three Petrarch Sonnets, it is the most frequently performed as a standalone concert piece.

Liebesträume No.3 (“Dream of Love”) is one of Franz Liszt’s most celebrated piano works.

Composed in 1850, it originated as one of three songs later transformed into lyrical piano pieces under the collective title Liebesträume (Dreams of Love).

The third piece in A-flat major became the most renowned of the set.

Based on a poem by German writer Ferdinand Freiligrath, the work can be viewed in three sections.

The opening unfolds with serene tenderness, its flowing melody evoking a dreamlike calm.

The middle section introduces richer harmonies and virtuosic passages, heightening emotional intensity,

before returning in the final section to a state of quiet reflection and transcendent peace.

Through this transcription, Liszt not only displayed his unparalleled pianistic mastery,

but also revealed a deeply human message:

“O love, as long as love you can.”

— a timeless exhortation to cherish love while it still lives.

Liszt’s Mephisto Walzer (Mephisto Waltz) stands as one of his most dazzling and symbolically charged piano works.

His music is famed for its virtuosic brilliance—long stretches of double notes, octaves, leaps, rapid runs,

and orchestral sonorities that seemed impossible on the piano.

These innovations had a tremendous influence on the European piano world of his time.

At the same time, Liszt’s works reveal a deep symbolic imagination.

In the Romantic era’s fascination with human emotion and the irrational spirit,

Liszt sought transcendence through dream and fantasy.

His music is imbued with passion, mysticism, and poetic contemplation—

expressing the tension between ideal and reality, the sacred and the sensual.

Mephisto Walzer was inspired by Goethe’s Faust, particularly the scene where Faust and Mephistopheles visit a village tavern.

Liszt composed four Mephisto Waltzes in total,

the first (S.514) written between 1860 and 1861, later revised for solo piano in 1881.

This waltz transforms Goethe’s dramatic vision into music filled with rhythmic drive,

chromatic intensity, and diabolical brilliance.

In this piece, the seductive power of the devil is rendered through a frenzied dance:

a quiet, mysterious prelude gives way to wild ecstasy,

as Faust is drawn from contemplation into temptation and desire.

The waltz’s whirling energy, alternating between rapture and ruin,

captures Liszt’s lifelong fascination with the struggle between the divine and the demonic.